What is your background and what are you working on now?

My background is in physics which I did at University of Hamburg in Germany, where I also took some classes in oceanography. In German we call the degree you get after five years a “diploma” but it’s the equivalent of a Master’s degree where you do a thesis project for all of your last year. I actually had no plans on becoming an oceanographer, but as things worked out, I was very happy to get to write my thesis on something other than elementary particles and relativity. Oceanography sort of became my escape route. I wrote my thesis on Denmark Strait overflow and even got to go to sea, it was a lot of fun, and I eventually ended up doing my PhD in the same research group.

After finishing my PhD, I took a little break from academia and for a time I worked as a programmer. After a while it got boring, and I ended up joining this research project looking at the ocean around the first German offshore wind park. However, just as I was spinning up on the job I got a call from my PhD advisor telling me that there were a couple of people up in Seattle that were looking for a postdoc, and they had inquired about me since we had met working on the Denmark Strait overflow. So, I applied and got the position, quit the wind park job and moved to Seattle. There I worked with James Girton and Matthew Alford on the abyssal overflow through the Samoan Passage, which connected to what I had been working on before. When Matthew was offered a professorship at Scripps, he offered me a job as part of his group, and I accepted and moved down to San Diego. Now I’ve been here at Scripps for almost a decade.

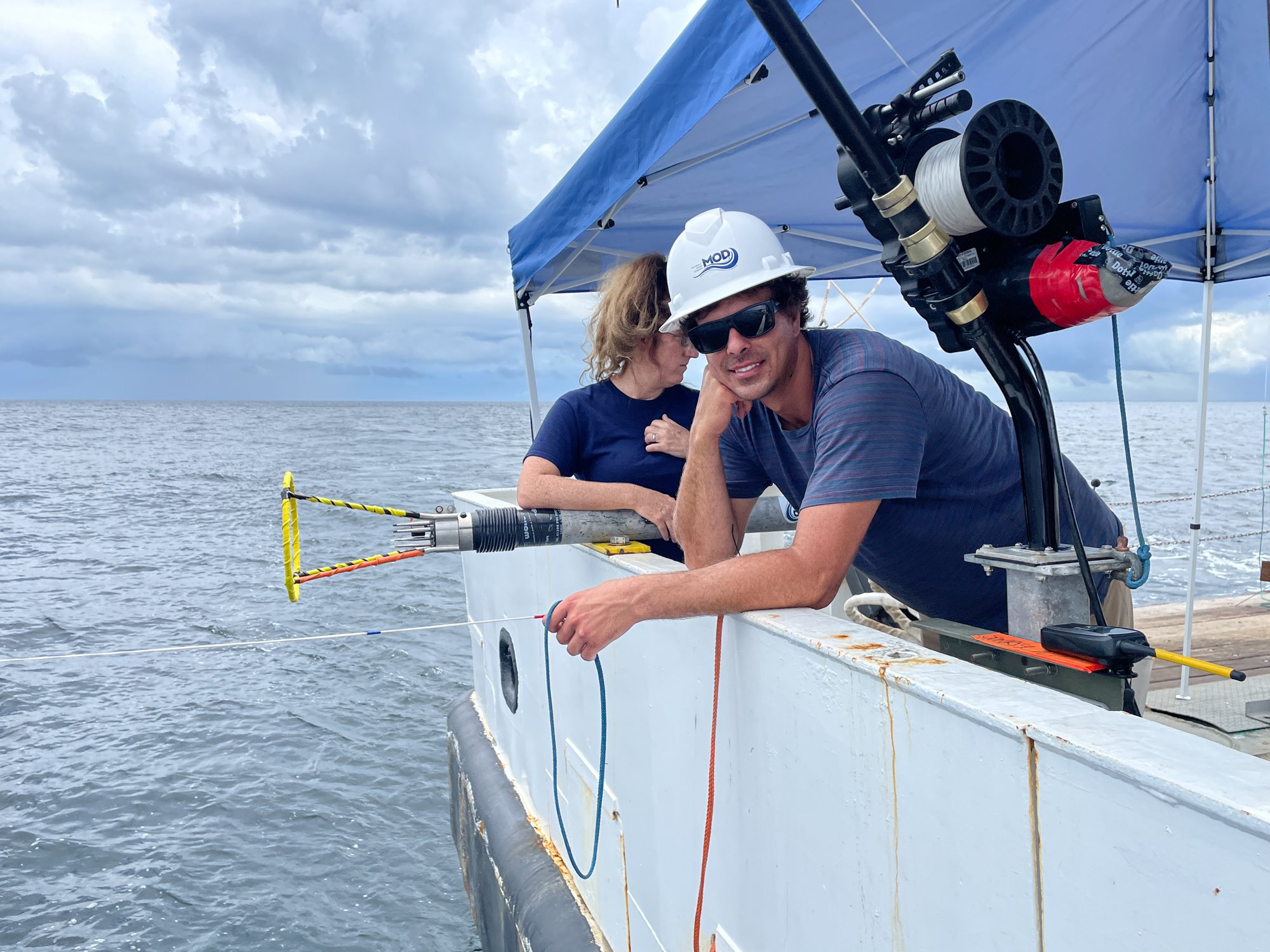

My current role in the MOD lab is a mix between a PI / researcher and an engineer. I’ve sort of specialized in subsurface moorings for oceanographic research. The typical set up is a heavy anchor to which you attach a line with different sensors to measure temperature, salinity, velocity, and at times even turbulence. The line is held upright by a buoy, but the whole system is submerged under water so we don’t have to worry about ship traffic or the force of surface waves. In my research I use a lot of this mooring data, but I also collect observations from the ship to look at the physical processes driving turbulence in the deep ocean.

What keeps you excited and interested in working in the field of oceanography?

The societal aspect of researching the ocean and climate. Although on a day-to-day basis it might not seem like one is having an impact, it still feels rewarding to do this kind of work and contribute to the understanding of our planet and climate. Through the work that we do we help improve climate models, and we see that they are getting rather accurate in predicting climate change which hopefully makes more people take them seriously.

A lot of the work I do is looking at turbulent mixing processes in the deep ocean which is one of the key elements that lead to model uncertainty when it comes to climate prediction. Having a better understanding of the physical processes in the deep ocean is important. However far removed from us they may seem they actually have a rather large societal impact.

I also really enjoy going to sea. Being in a confined space with people for a long time is like a little social experiment every time, but often it’s great fun. Especially when you get to work with great people which is usually the case.

When you were a kid, did you expect to be a scientist or engineer?

No no, when I was a kid, I wanted to be a train conductor. Later, as a teenager, I had no idea what I wanted to do, and it was my high school teacher that suggested I go into Geosciences. I ended up taking a bit of a roundabout way to get there I suppose. My parents studied math and physics respectively though, so going into science was not a strange concept when I was growing up.

Were there any particular things from your childhood that drew you to study the ocean?

We always spent the summers on a little island off the coast of northern Germany, one of the East Frisian Islands that stretch from Germany all the way towards the Netherlands. My parents would pitch a tent at the beginning of the summer, and me and my brother would spend the better part of our holidays there right on the beach. In a way I guess I grew up on the ocean, at least during the summers.

What skills or abilities do you think are useful when going into oceanography or academia in general?

Curiosity is important, but you also need to be able to deal with disappointment. It’s good to be able to work at least partially self-motivated and not be afraid of struggling with things, difficult moments and emotions included. Of course you can ask people for help and it’s almost always a team effort, but ultimately someone has got to do the work. If you’re a good writer and coder that helps too, and if you enjoy that it makes your work more fun, same with logical thinking and reading. But these are all skills you can acquire as you start working. Ultimately though I think you need to be at least a little bit interested in the work.

I think it’s also important to recognize that you’re not going to be an expert in all the things you do as a researcher. You work in a field that is very specialized but also overlaps with other fields. For example, if you are an observational oceanographer you’ll still be working with modelers, not to mention engineers, and it can sometimes feel like it’s too much to learn and take in being surrounded by people who are experts at their thing. But you do not have to master it all to be able to collaborate well, plus it’s part of what makes work interesting, that there are always opportunities for growth.

What does a typical work-day look like for you?

On a good day I get to bike to work, I am a climate researcher after all so that’s something I like to do, and then I typically start off by doing some paper reading. Then there might be some more engineering-like work, planning a new experiment, what we need to build, cruise logistics and more, likely I’ll meet with the MOD engineers to coordinate. Hopefully I eventually get to do some data analysis and make some figures. In an ideal world I then move those figures into a paper draft, but of course I don’t do all these things every single day. On any given day it is also likely that I’m connecting with other researchers in the MOD lab, or at other institutions, to collaborate on proposals or papers, and that is something I enjoy.

What drew you to work at Scripps?

It’s so hard to leave because the weather is so good? Jokes aside, it is a wonderful research community full of mostly good people who really put in an effort to make Scripps a fun and welcoming environment.

Is there a particular scientist or person that inspires you?

This sort of feeds into my previous answer but Jen MacKinnon is a person who is doing such a great job doing awesome research, while at the same time also putting in a lot of effort into the community. It is no coincidence Scripps is a nice place to work at, there are many people who work to make it so, Jen included. She manages to do amazing research AND does a great job at making Scripps more welcoming, diverse and inclusive which is something I really appreciate.

Do you have a fun fact that you'd like to share that not everyone knows about you?

Well, full honesty, the project that I was about to join working on an offshore wind park? A very big reason I was attracted to that job was because the name of that project was Research at Alpha Ventus, or RAVE for short. As someone who enjoyed, and still enjoys, a good techno party I thought it was brilliant to be working at “RAVE”, it almost felt like it was meant to be…

Written by Kerstin Bergentz